Biography

*April 18, 1900 in Cogogne; † May 26, 1970 in Heidelberg.

Father: Adam Schneider.

* 29.11.1871 in Bochold near Borbek [Essen]: merchant. † before 1929 in Karlsruhe.

Mother: Elise Schneider, née Kratz.

* 25.02.1873 in Daubach/Westerwald. † 10.07.1955 in Heidelberg.

| 1900-1918 | Born in Cologne (1900). In 1903 the family moves to Karlsruhe. During the First World War, L.S. serves briefly as a soldier. He becomes a revolutionary and spartakist and breaks with the Catholic Church for political and ideological reasons, remaining however, according to his own statement, „a deeply religious person and at the same time a socialist“. | ||||||

| 1919-1924 | Studies German literature and theatre at Munich university. Contacts there to the comedians Karl Valentin und Liesl Karlstadt. In leisure time acting and mountain hiking. Intensive engagement with psychoanalysis and by this awakening interest in Judaism. Drop out of his university studies. |

||||||

| 1924-1933 | 1924 marriage to Gertrud Schimmelburg. (* 08.08.1903 in Zurich; † 10.05.1934 Saint Martin-le-Vinoux; accident during a climbing tour on Mont Blanc).Gertrud’s father Hugo Schimmelburg provided significant financial support for LS’s publishing project, perhaps making it economically viable in the first place, as can be seen from a letter to his granddaughter Marianne Gouray, née Wilmersdoerffer (Gertrud Schimmelburg’s niece).

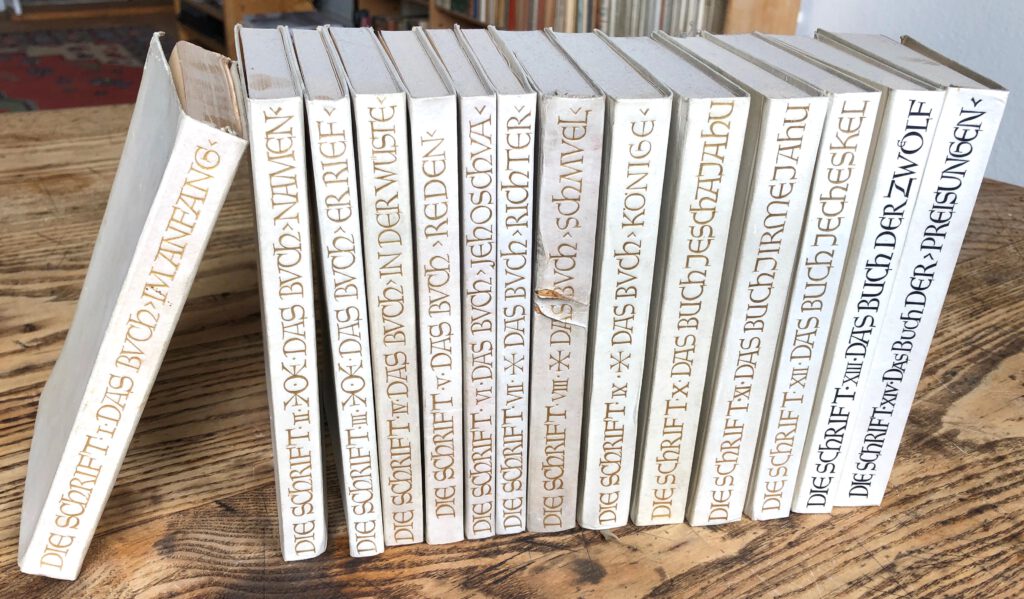

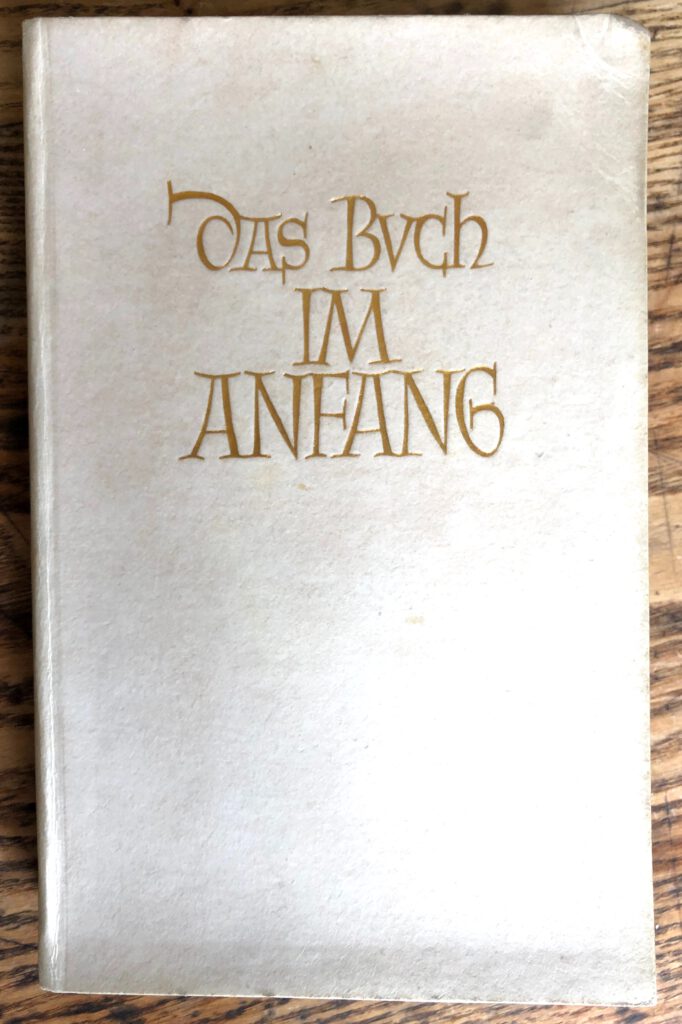

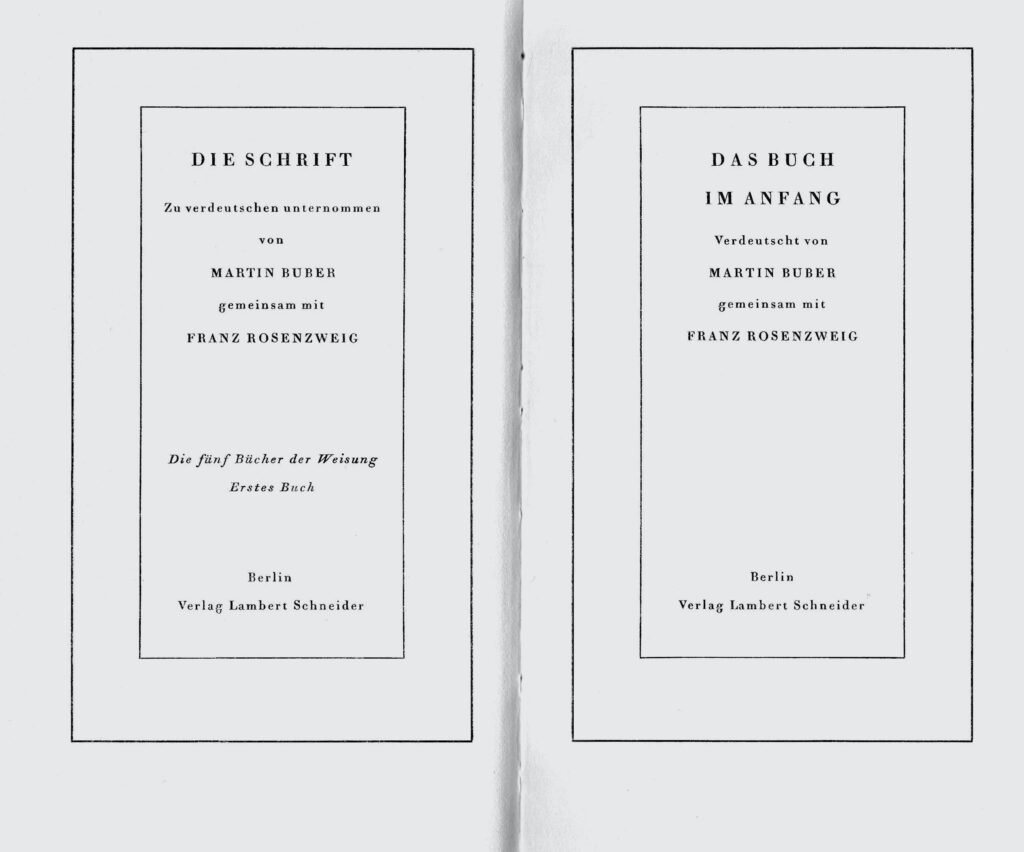

Relocation to Berlin-Dahlem into a stylish modern domicile in Schorlemer Allee. Foundation of the Lambert Schneider publishing house: as a 25-year-old then with a glowing enthusiasm and a deep interest in Judaism, ecumenical and political questions, belles-lettres and, last but not least, typography and book design in which Jakob Hegner becomes decisive for him. This impetus and these interests were to shape the publishing house over the decades from the very beginning.  In 1925 Lambert Schneider makes contact with the then most famous Jewish religious scholar Martin Buber in Heppenheim and presents his request to finally publish a literal and authentic Jewish translation of the Old Testament from Hebrew into German in his publishing house. Buber agrees on the condition that the historian and philosopher Franz Rosenzweig is involved as a co-translator. In the following years of cooperation, Buber, Rosenzweig and L.S. become close friends. This long time project, which is challenging for the publishing house not only in terms of philology and religious studies, but also financially, will determine the further course of publishing activities. From 1925 to 1931 11 volumes of this translation of the Old Testament are published by L.S., then a further three by Schocken Publishing House (see below); the project was not completed until 1962. |

||||||

| A selection of the fist titles of the just founded publishing company shows what moves the young publisher: | |||||||

| 1925 | Die Schrift [Biblia]: Zu verdeutschen unternommen von Martin Buber gemeinsam mit Franz Rosenzweig. (1) das Buch im Anfang. [Genesis].

Immanuel Kant: Träume eines Geistersehers, erläutert durch die Träume der Metaphysik. Neue Deutsche Druckschriften: Ehmke Antiqua. Fred Neumeyer: Ausrast und Wanderschaft. Gedichte. |

||||||

| 1926 | Die Kreatur. A quaterly publication (three years published), edited by Martin Buber [jew], Viktor von Weizsäcker [protestant] und Joseph Wittig [catholic].

Jehuda Halevi: 92 Hymnen und Gedichte. Franz Rosenzweig: Die Schrift und Luther. Eugen Rosenstock: Religio depopulata. Zur Ächtung Joseph Wittigs [The philosophical and political treatise turns against the outlawing and excommunication of Joseph Wittig as a Catholic theologian and Christian archaeologist who had argued against the practice and theology of confession]. |

||||||

| 1927-1933 | To these religious and philosophical topics come specifically political ones, e.g. Gustav Landauer’s writings “Aufruf zum Sozialismus [Call to Socialism]” and „Aufsätze über den Krieg [Treaties on War]“.

Martin Buber’s and Franz Rosenzweig’s translation of the Bible, published in separate volumes, from 1925 on by Lambert Schneider. |

||||||

| 1934 | Marriage to Marion Schleuning (* June 23, 1903 in Berlin; † June 1, 2000 in Hamburg).

Marion Schleuning had lived in a shared apartment in Berlin with the painter and illustrator George Grosz and acquired advertisements for the magazine Die Weltbühne and was therefore well known to Karl von Ossietzky and Kurt Tucholsky. Through her work she got to know the publisher Lambert Schneider. Both were deeply convinced “anti-Nazis” in terms of their socialization, an attitude which will not change in the following years.

|

||||||

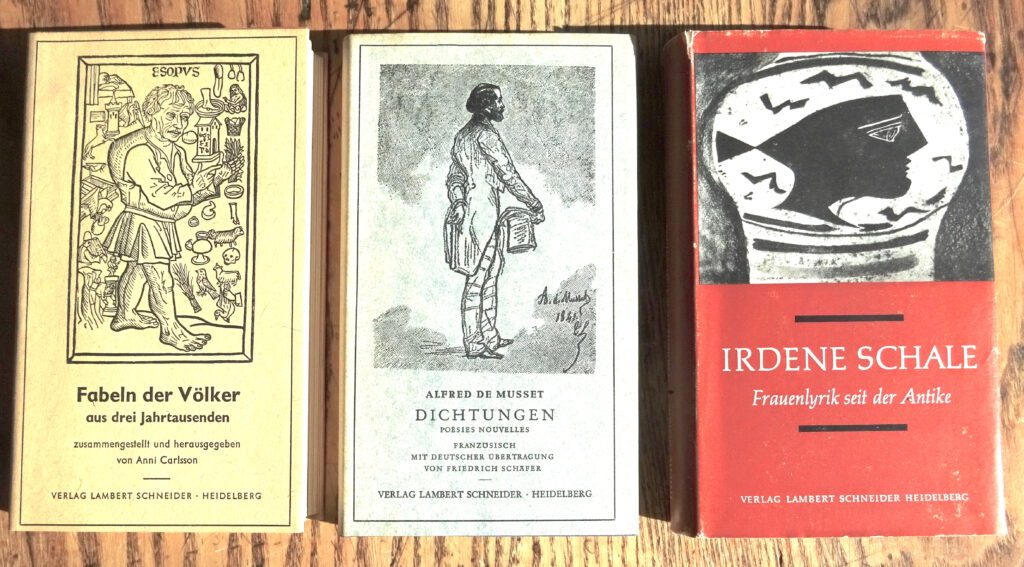

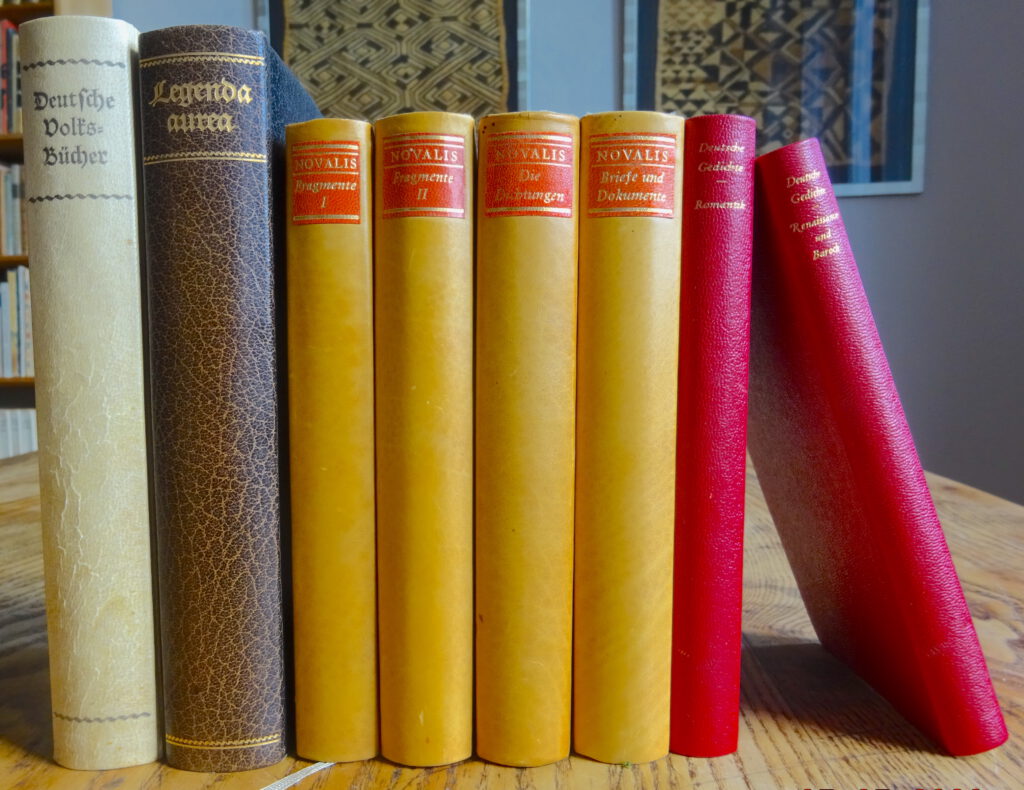

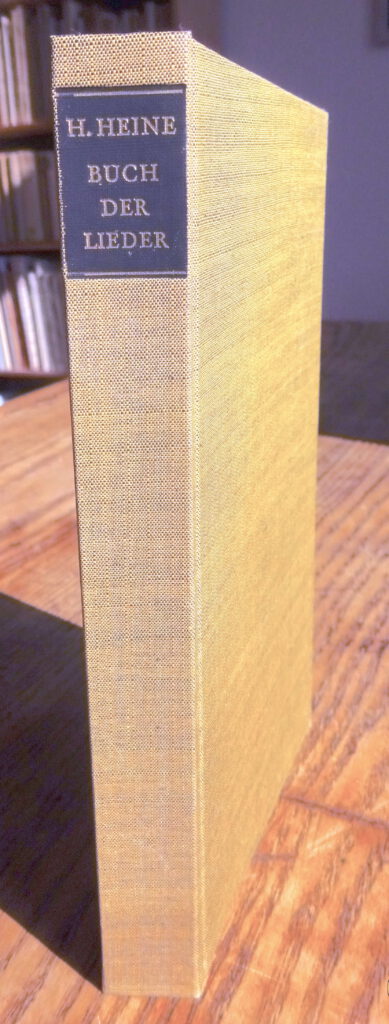

| 1933-1945 | During the National Socialist phase of Germany, the publishing house can no longer bring out any new titles of the type mentioned. The books that have already been published are however delivered until 1936/37. Instead philosophical texts appear, but above all classics of world literature in elegantly simple editions: Gollias, Lieder der Vaganten [= Carmina Burana]; Aristophanes, Comedies; Plato’s works; Shakespeare’s works and those of his contemporaries; Blaise Pascal; Novalis; various poetry anthologies. Some of the titles published at that time are still edited by befriended Jewish scholars such as Erich Löwenthal, but their participation can no longer be noted in the printed edition.

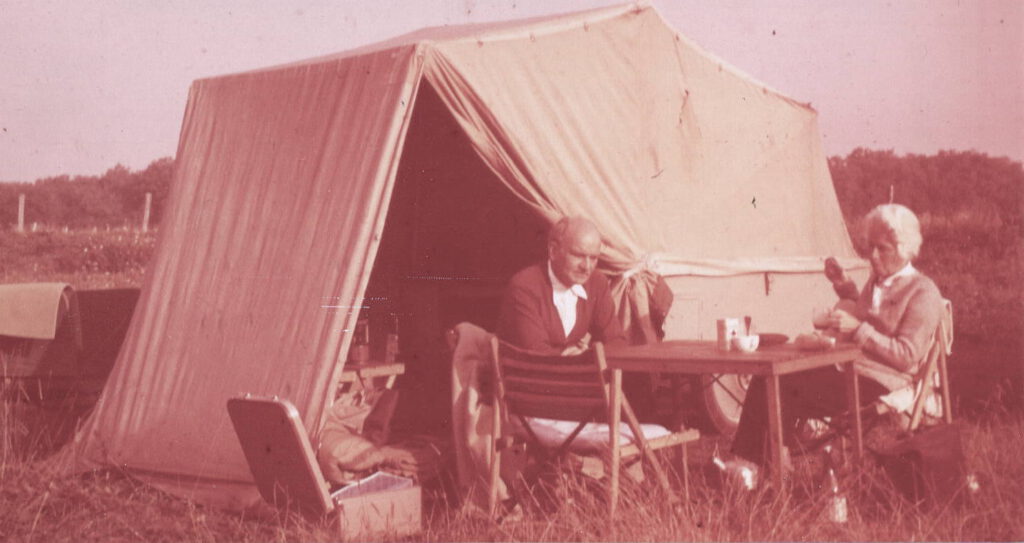

As a result of the Great Depression, but also due to restrictions on the part of the Nazi regime, the activities of the publishing house are reduced to a minimum. In this situation, on the advice of Leo Baeck, Lambert Schneider turns to Salman Schocken: the founder and co-owner of a huge department store chain, at the same time philanthropist, collector of rare books and manuscripts, and owner of the newly founded Schocken Verlag in Berlin. L.S. becomes head of this publishing house in 1932 and from then on supervises the book production of Schocken-Verlag in addition to his own publishing house. He is specifically entrusted with the Schocken library, in collaboration with Moritz Spitzer, an indologist and brilliant typographer. In 1938, ‘Aryans’ were banned from running Jewish businesses, including L.S., which is why Moritz Spitzer took over the management of the publishing house. In the same year the Schocken Verlag is forcibly closed; Spitzer emigrated to Palestine in 1939. A lifelong friendship has developed between Lambert Schneider and Moritz Spitzer.  Other important friends and companions for Lambert Schneider during this time and later are Michael Brink (Catholic journalist; collaborator with resistance groups; godfather of his son Lambert; imprisoned 1944/45 in the Ravensbrück and Sachsenhausen concentration camps), Bruno Henrich (art historian, private scholar), Volodja Leventon (banker, emigrated to the USA in 1937), Eva Zilcher (actress), Hans Haustein (photographer), Georg Muche (painter, Bauhaus artist), as well as the authors of the publishing house Ernst Michel, Ernst and Sophie Wasmuth and Fred Neumeyer (Art historian; emigrated to the USA). L.S. and his wife Marion are well informed through their Jewish friends and their friendships with liberal-minded fellows as well as through contacts with the Berlin Jewish community about the atrocities of the Nazis, not only in Germany, but also in the areas conquered by the Wehrmacht. Both must have been a brave and complementary couple in those years: he enthusiastic and highly committed, she pragmatic and always courageous and willing to take risks. During the summer months both undertake extensive art trips with tent and tent trailer to Italy and France, sometimes with the friends mentioned.

In 1938 and 1940, L.S. is drafted into the Wehrmacht for a few months at a time, but is quickly released again for publishing work (UK, ‘Unabkömmlichstellung’ [‘indispensable’]). Assigned to the Stablack prison camp (East Prussia) for two months, he experiences with horror the treatment of prisoners of war from Belgium and France, whose deaths through freezing and starvation were consciously accepted. In 1943, the publishing office in Berlin and the book storage in Leipzig are bombed; the family moves to the countryside in the Eifel: first to Nideggen (still with furniture and part of the private library), then – after the house has been destroyed – to Stärklos, now in a cellar of a house of unwilling farmers. In the last year of the war, L.S. receives a draft order for the ‘Volkssturm’. But in the winter of 1944/45 he gets saved from this and from reprisals of GESTAPO through another order, now from the Todt Organization, mediated by the photographer Oswald zu Münster and a certain Walter Böcker. He is ordered to drive all over Germany on trains and look around for paper stocks that in reality no longer exist. So, of all people, officials of that Nazi organization, who knew his sentiments and publishing activities very well, have protected him in the last phase of the war. |

||||||

| 1943 | Birth of the son Lambert Adam Schneider. | ||||||

| 1945-1950 | Already in the last years of the war and then in the times of need afterwards, the small family grows into an extended family by taking in children of friends and relatives – including: Bärbel Kleine (daughter of his lawyer friend Heinz Kleine), later Karola Sander and – already as a teenager – from 1945 to 1954 Waltraut Schleuning (a niece of Marion Schneider), who later also works in the publishing house. From 1949 until her death in 1955 L.S.’s mother Elise, née Kratz, lives in the household of Marion and Lambert Schneider.

After the conquering of the Eifel by the American armed forces in 1945, L.S., whose whereabouts had been researched in the USA, is immediately entrusted with the continuation of his publishing house by the American military responsible for cultural issues. He is given the publishing license number 3 in Germany. On the advice of Alfred and Marianne Weber in Heidelberg, he decides not to return to Berlin, but to continue his publishing work in Heidelberg. For a short time he also becomes entrusted with the provisional management of the Carl Winter University Press in Heidelberg. On November 10, 1945, the first issue of the monthly Die Wandlung is published (as a joint project of by both publishing houses). It is the calling card of the new cultural beginning. The contributors are Karl Jaspers, Werner Krauss, Alfred Weber and Dolf Sternberger. On the initiative of Alfred Weber, people from different political camps come together in Heidelberg to form the “Aktionsgruppe zur Demokratie und zum freien Sozialismus [Action Group for Democracy and Free Socialism]”, of which Lambert Schneider becomes chairman.

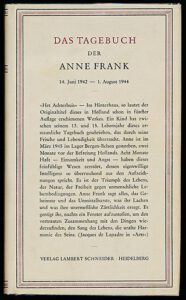

In the post-war period, Lambert Schneider plays a key role in the drafting and elaboration curricula based on democratic values and respective examination regulations for training as a publisher and bookseller; he is the chairman of the examination committee in the Heidelberg/Neckar district. During the first post-war years, an enormous amount of titles appear in close succession in the publishing house of L.S. – due to his impeccable behavior during the Nazi era and due to a lack of ‘denazified’ publishers in Germany by then, these include titles wide beyond the traditional/normal spectrum of the company. E.g. Süddeutsche Juristenzeitung (1946); Karl Jaspers, Die Schuldfrage [The Question of Guilt] (1946); Walter Hallstein, Wiederherstellung des Privatrechts [Restoration of Private Law] (1946); Gustaf Radbruch, Gesetzliches Unrecht und übergesetzliches Recht [Legal Injustice and Supra-Legal Law] (1946); Die Friedensverträge mit Italien, Rumänien, Bulgarien und Finnland [The peace treaties with Italy, Romania, Bulgaria and Finland]; Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch [Civil Code]. Furthermore individual publications from the field of psychology as well as the journal Psyche – Ein Jahrbuch für Tiefenpsychologie und Menschenkunde [Yearbook for Depth Psychology and Human Studies [4 volumes], edited by Alexander Mitscherlich and Fred Mielke. Finally, in those years often reviled and hostile, writings to come to terms with the ‘medical’ Nazi crimes: Alexander Mitscherlich and Fred Mielke, Das Diktat der Menschenverachtung. Eine Dokumentation vom Prozeß gegen 23 SS-Ärzte und deutsche Wissenschaftler [The Dictate of Human Contempt. A Documentation of the Trial against 23 SS-Doctors and German Scientists] (1947); Viktor von Weizsäcker, Euthanasie und Menschenversuche [Euthanasia and Human Experiments] (1947); Alexander Mitscherlich and Fred Mielke, Wissenschaft ohne Menschlichkeit. Medizinische und eugenische Irrwege unter Diktatur, Bürokratie und Krieg [Science without Humanity. Medical and Eugenic Aberrations under Dictatorship, Bureaucracy and War] (1949).  1949 Anne Frank’s father comes to Lambert and Marion Schneider in Heidelberg with the diary manuscript of his daughter who died in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in 1942/44. Children’s diaries were not at all part of the publisher’s spectrum of content, but after reading the typescript, the decision was soon made to publish this document. So the first German edition of Anne Frank’s diary is published by Lambert Schneider, initially hardly noticed and at best greeted with hostility at the time: Das Tagebuch der Anne Frank. 14. Juni 1942 bis 1. August 1944. Mit einer Einführung von Marie Baum. Aus dem Holländischen übertragen von Anneliese Schütz (1950). In addition to the titles mentioned, the focus of the publishing production of those years lies on the careful publication of world literature in German translations, partly also bilingual (including Charles Baudelaire, Clemens Brentano, Paul Claudel, Arthur Rimbaud) and of German poetry; in addition anthologies come out such as Sturm und Drang; Poems of the Romantic Era, etc.). Essays and poems by author friends also appear, including: Walther Bulst, (latinist); Petra Clemen (graphic designer); Wilhelm Lehmann (poet); Fred Neumeyer (art historian); Walter Schwagenscheid (architect); Dieter Wyss (psychiatrist); Ewald Wasmuth (philosopher).

|

||||||

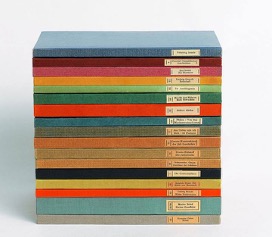

| 1950-1970 | The period up to 1965 is summation, an adding up and rounding off. Numerous new interesting titles appear, but the intellectually and socio-politically most innovative phase of Lambert Schneiders enterprise of publishing comes to an end around 1952. More writings by Martin Buber appear (Urdistanz und Beziehung, 1951; Die chassidische Botschaft, 1952; Zwischen Gesellschaft und Staat, 1952; Schriften über das dialogische Prinzip, 1954; Schuld und Schuldgefühle, 1958). An edition of Martin Buber’s complete works including his extensive correspondence is started, Franz Rosenzweig‘s important book Stern der Erlösung is in the program (1954, now 3rd edition; originally published by Schocken-Verlag Berlin), as well as the monumental essay of Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy, Die Sprache des Menschengeschlechts. Eine leibhaftige Grammatik in vier Teilen (1963).

The core of the publisher’s production – in particular important for sales – lies in aesthetically appealing, simple and modern designed classic editions, often in parallel as linen and leather bindings, sometimes with parchment bindings. Among others: Plato’s works; Shakespeare’s Works; Shakespeare’s Contemporaries; the Legenda Aurea of Jacobus de Voragine; Carmina Burana; Abelard; Nachtwachen des Bonaventura; Verlaine; Baudelaire; Rimbaud; Mallarmé; Byron; Rossetti; Blake; Shelley; Keats; Novalis; August Graf von Platen; Wackenroder. Poetry anthologies such as: Deutsche Gedichte des 16. und 17. Jahrhunderts; Deutsche Gedichte der Klassischen Zeit; Deutsche Gedichte der Romantik und des Jungen Deutschland.

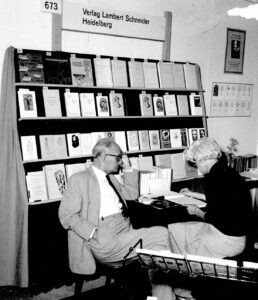

Lambert Schneider not only selected the titles that he published himself (often after discussion and consideration with his wife Marion), but also mostly designed the books himself. Sitting at his desk in the evening when the day’s work was done he edited the texts, chose the printing types that he thought were suitable, determined the layout of the pages, and selected the papers for printing. The cover designs were discussed with the respective bookbinding firms (in Heidelberg usually Willy Pingel). All printing and binding work was outsourced because the publishing house did not have its own printing plant, neither in Berlin nor later in Heidelberg. It was rather a one-man company, especially after the war. When the business was booming, an accountant was hired and, if necessary, a second employee for various tasks. The ‘residence’ of the publishing house, which some colleagues and foreign authors even from abroad wanted to visit from time to time, consisted of two rooms in the basement of a block of flats, in which, higher up, the apartment and the precious private library were located; the book warehouse was housed in three garages in the backyard. So the actual publishing work took place in the in L.S.’s private study on those evenings, when there were no conversations or listening to music or celebrating with friends over wine and cigarettes. Books not only have to be produced but also sold. It is Marion Schneider who has taken on this difficult and thankless task for decades. As a representative of the publishing house, she travels all over Germany with a heavy specimen copy bag and visits the booksellers to get them to buy books that are often difficult to sell. Not only with a view to the time of hardship and war, L.S. in his Publishing Almanac of 1965 annotates: ” The greatest thanks I owe to my brave wife Marion, then and now”.  From 1951 to 1965 Lambert Schneider acts as representative of the German Book Trade Association and therefore spends part of his working time in Frankfurt. There are also tasks as a consultant to the German Research Foundation (DFG) and as a member of the jury for the selection of the Villa Massimo Prize winners in Rome, as well as co-initiator and organizer of the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade; the respective speeches about the award winners and the speeches by the award winners themselves are published by L.S. Also the publications of the German Academy for Language and Poetry and – at the suggestion of Theodor Heuss – the speeches and memorials of the order Pour le Mérite come out from L.S.’s publishing house. In the 1960s, L.S. gives evening lectures and discussions in Heidelberg that underline once more the impetus of the now aged publisher and which have received a lot of attention and have been extensively reviewed in the press: e.g. Forays through Sturm und Drang literature; The young Goethe and his era; Günter Grass > The Tin Drum<. In his almanac Rechenschaft. 1925-1965 L.S. gives insights into his publishing activities, whereby he mainly lets his authors speak; a list of the titles published up to this point can also be found here.

From the mid-1950s on, Lambert Schneider and his wife Marion resume their trips to the south: still with a tent or trailer tent, and now with their son Lambert and often with their friends Jura Lewenton and his then wife Hanne. No Romanesque capital, no marble pulpit, no fresco, no painting in a gallery, no excavation site, no matter how remote, that is not visited, examined in detail and also photographed. The trips take the family through Germany, Austria, France, Spain, Italy and Greece and are carefully prepared by L.S., because back then there was little useful art historical travel literature yet. Some art venues are not accessible by car, but have to be ‘hiked’. In the Abruzzo or the Spanish Pyrenees, for example, some remote churches can only be reached after a long walk and can only be visited once you have found the right goatherd with the appropriate key.

Lambert Schneider dies of cancer, which he contracted from smoking for decades, on May 26, 1970 among his relatives. Despite his early and never revoked exit from the Catholic Church and the associated excommunication, he is blessed by Richard Hauser, the dean of the Jesuit Church in Heidelberg, a good friend of the family and author of the publishing house. He is buried in the Heidelberg mountain cemetery. Lambert Schneider and Marion Schneider’s gravestones were later transferred to Ohlsdorf cemetery in Hamburg. After L.S.‘s death, the publishing house was continued by the publisher Lothar Stiehm under the old publisher’s name and thereafter transferred in 1999 via Heinz M. Bleicher to the Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft Darmstadt, while the rights to the complete works of Martin Buber had previously been assigned to the Gütersloh publishing house. The archive (with almost the complete set of the published editions as well as part of the publisher’s correspondence) has been housed in the German literary archive in Marbach (Deutsches Literaturarchiv Marbach) since 2001, further correspondence can be found in the Israel Museum, Jerusalem. Marion Schneider lived on in Heidelberg after the death of her husband, moved to Hamburg in 1985 and spent her last years with her son Lambert Schneider and his wife Monika Debes-Schneider. |

||||||