* June 23, 1903 Berlin; † June 01, 2000 Hamburg.

| Father: Wilhelm Theodor Ludwig Schleuning. Civil engineer; inventor. *1852 Heidelberg †1914 Magdeburg.

Mother: Marion Schleuning, née Rosenplaenter. *1867 New York †1947 Uelzen.

|

|

| 1903-1923 | As a child, Marion grew up with her two brothers Hans and Wilhelm (Willi) and her sister Theodora (Dolla) in Berlin. Initially she grew up in an upper-class milieu, however, after the death of the father in 1914, however, the family fell into poverty. The family silver was exchanged for food etc. The mother found the forced changeover challenging. But for Marion, the sale of table silver and other bourgeois props that she had to carry to the pawn shop provided a certain sense of liberation. While the brother, Hans, was more of a German-national mind, his siblings, Marion and Willi, were tired of the old empire, both politically and in its plush style.

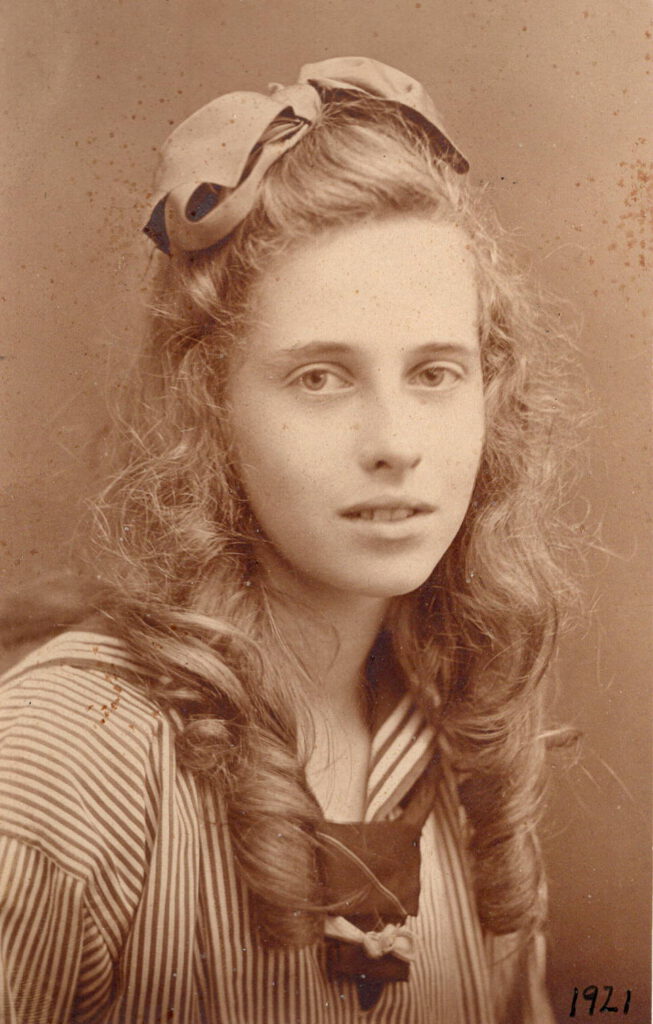

Even as a child, Marion had to take care of the hose maintenance, and only had time to go to school until she reached secondary school. Nevertheless, even as a teenager she was already familiar with the avant-garde cultural life in Berlin, with regard to literature, theater as well as the music scene. She also spoke English and French fluently, almost perfectly. In order to escape domestic poverty and at the same time to support the family, she embarked on the SS Lapland via Southampton to America in the summer of 1921 when she was just 18 years old (the document of her ship passage is preserved in the Bremen Übersee-Museum). There she initially stayed there, near Baltimore, with the family of a distant relative as an au pair. However, annoyed at the landlord, she soon packed her bags again, went into business for herself and moved into a room in New York. She made just enough through odd jobs such as cleaning and editing to live a modest life and send home a few dollars a month. She also got herself two driver’s licenses in New York: one for Ford automobiles, as she later reports, and one for other cars. However, as a result of loneliness, she remained only a year in Manhattan before returning to Berlin. |

| 1923-1945 |

In Berlin she kept close contact with her musician brother Willi and became involved in the progressive cultural life of the Weimar Republic; this is how she then learnt of George Grosz, Kurt Tucholsky and Carl von Ossietzky. She worked for the magazine Die Weltbühne, acquiring advertisements from publishers for this paper. It was through this activity that she met the publisher Lambert Schneider. |

| 1934 Marriage to the publisher Lambert Schneider.

Marion was her husband’s true supporter and partner, not least in a political sense: any form of membership in Nazi organizations or even closeness to them was unthinkable, and relationships with Jewish and other anti-Nazi friends and authors were maintained by both of them. The survival of the publishing house in those years is owed a lot to her, as L.S. has repeatedly has emphasized. L.S. and Marion were well informed about the atrocities being committed by the Nazis right from the beginning, not only in Germany, but also in the areas conquered by the Wehrmacht. They were able to learn about these atrocities through their Jewish friends and their friendships with liberal-minded fellows, as well as through contacts with the Berlin Jewish community. Both must have been incredibly brave and a complementary couple in those years: he enthusiastic, highly committed to Judaism, ecumenism and liberal socialism, she pragmatic, always courageous and willing to take risks. In the summer months, the two of them went on extensive trips to Italy and France with a tent or tent trailer, sometimes with friends. |

|

| 1943 Birth of the son Lambert Adam Schneider. | |

| 1945-1970 | Towards the end of the war, the family moved from Berlin to the countryside in the Eifel. Marion took the children of relatives and friends into the family, including Bärbel Kleine, daughter of the lawyer friend Heinz Kleine, and Franziska Düren. Grandmother “Ija” (Elise Schneider, née Kratz) also found refuge in the family. After the end of the war, the nieces Waltraut Schleuning and Irmgard Schleuning resided for a few years in the Schneider house in Heidelberg, and later Karola Sander, whose single mother the Schneiders had met by chance. Then and later, Marion Schneider stood by many people in need and encouraged them to try life again and start something new. Wether after traumatic war experiences, a failed love affair, and abortion or a failed exam, she would take them by the hand and say: “It’ll be fine, I know something like that, I’ve experienced something similar, and now we’re doing this and that … and I’ll help you.” Perhaps the word “courageous” in all shades of its meaning is the adjective that characterizes Marion most succinctly. Despite all her love and caring, her their educational approach was at times quite strict.

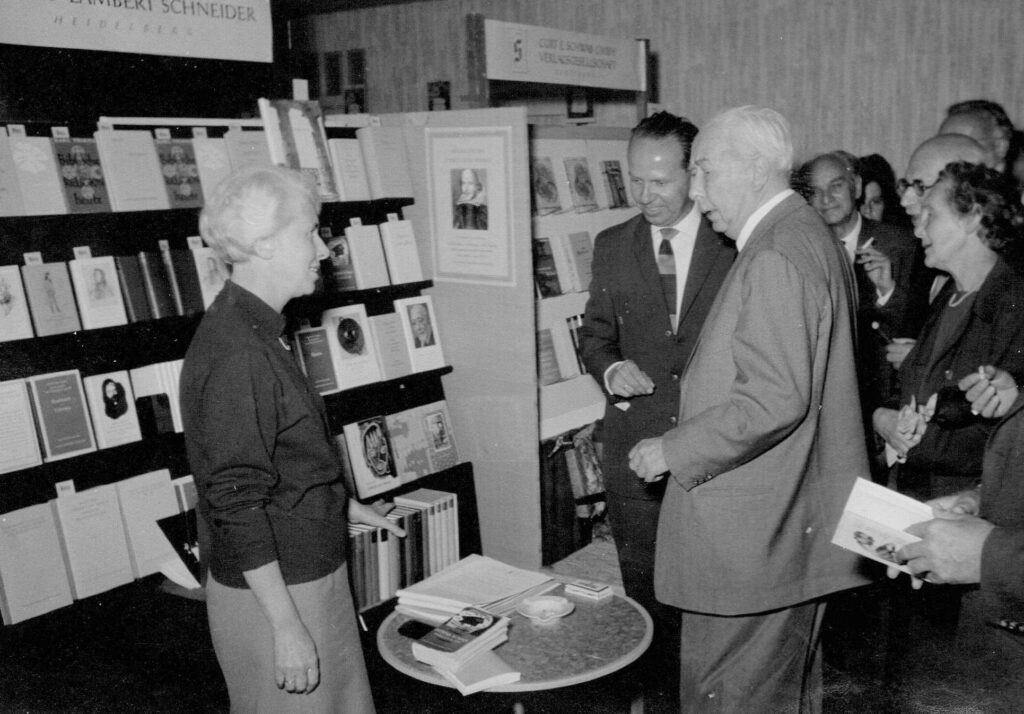

Immediately after the end of the war, the publishing house at Heidelberg developed an enormous productivity (see the biography of the publisher L.S.). But books not only have to be produced, they also have to be sold. It is Marion who took on this part with vigor and enthusiasm for decades. As a representative of the publishing house, she traveled across Germany for two months in spring and autumn with a heavy specimen copy bag and visited the booksellers to get them to buy books that were often difficult to sell: an arduous and often thankless task. Not only considering the events that occurred during the time after hardship and war, L.S. notes in his almanac published in 1965: “The greatest thanks I owe to my brave wife Marion, then and now”.  Since the mid-1950s, L.S. and Marion resume their trips to the south in the spring and summer months: to France, Italy and soon to Greece – now with their son Lambert. In the 1950s, Marion Schneider, who had hitherto been entirely atheist, turned to the Catholic faith, encouraged and motivated by Eugen Biser, an author of the publishing house and religious educator of the son; she converted to Catholicism and found a new spiritual home there. Over the years this close affinity with Christianity and in particular Catholicism waned again. What remained, however, was a great modesty in relation to one’s own knowledge of transcendence. |

| 1970-1985 |

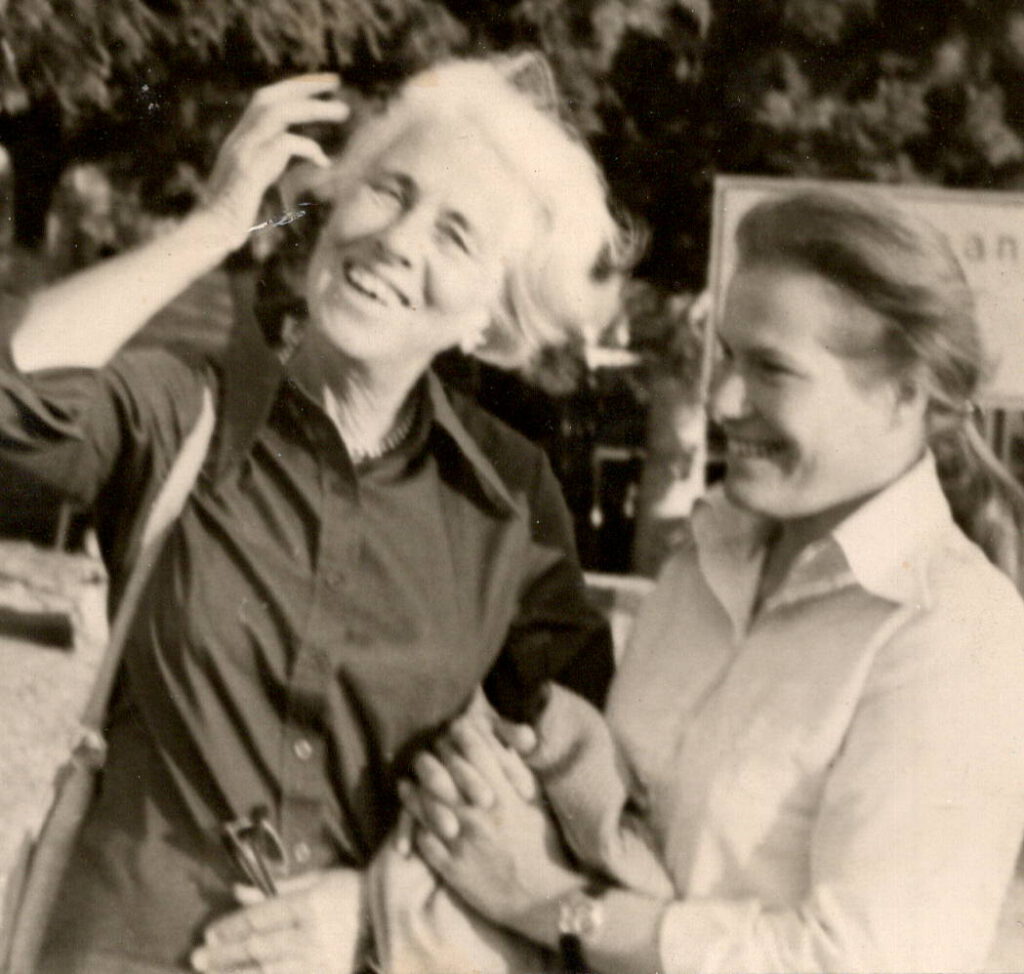

After the death of her husband in 1970, Marion continued to live in Heidelberg. In this phase, too, she took on relatives and friends who were currently in a crisis, letting them live with her and supported them with care and advice, fo example, in 1980/81 her nephew Andreas Kasack. For several years she took Mehmet Alpaslan, the child of a friend of her now adult foster daughter Bärbel Schmidt (née Kleine), into her care. Marion regularly spent the summer holidays with her foster child Bärbel Schmidt and her husband Harald in Istanbul, sometimes also in Side on the Turkish south coast. Increasing demine of her eyesight and later also hearing impairment greatly affected her life, which had become lonelier after the loss of her husband and the death of almost all of old friends. But even when she is very old, she was still making new friendships, for example with the translator Dora Fischer-Barnicol, whom she met through the publishing house. |

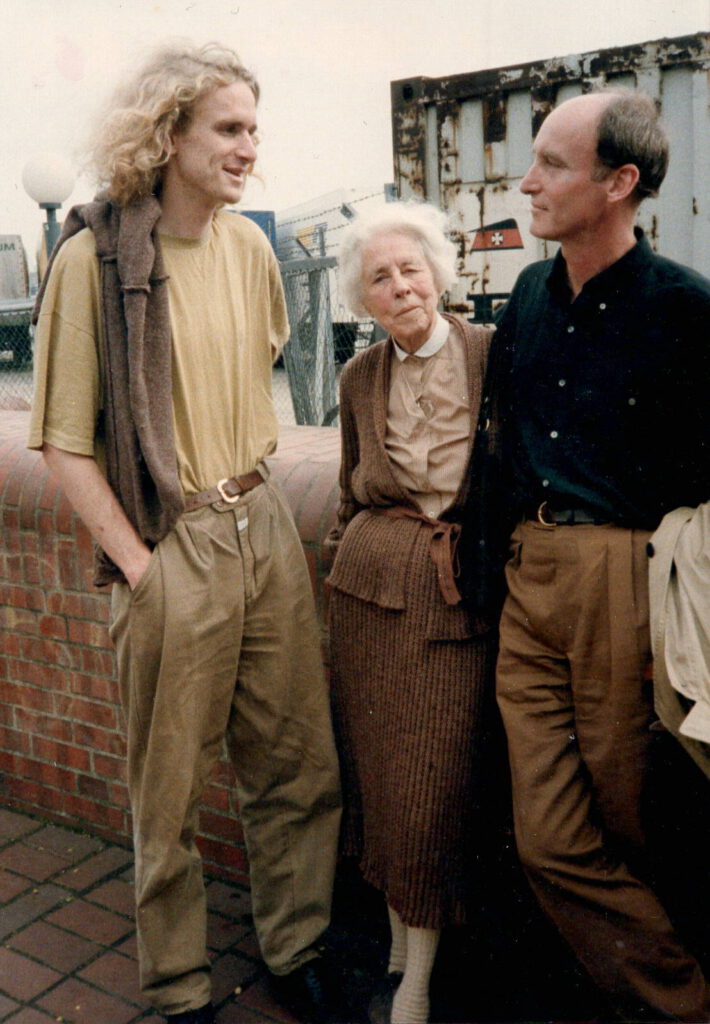

| 1985-2000 | In 1985 Marion Schneider moved to Hamburg to be close to her son Lambert and his family. Although already half blind, she was still committed to helping Turkish children there, whom she regularly supported with their homework after school. She spent her last eight years in the family of her son Lambert and his wife Monika.

When she could no longer read herself, she resorted to using audiotapes to pass time. But poetry lived on in her as a treasure and comforted her. She knew many poems by heart and would often hum them softly to herself. Sometimes, however, she would want them to be read aloud, for example, at the hour of her death, the famous Goethe poem Wanderers Nachtlied, particularly beloved by her – a poem relating to death, which can be found in her husband’s anthology of German poems of the classical period.

|